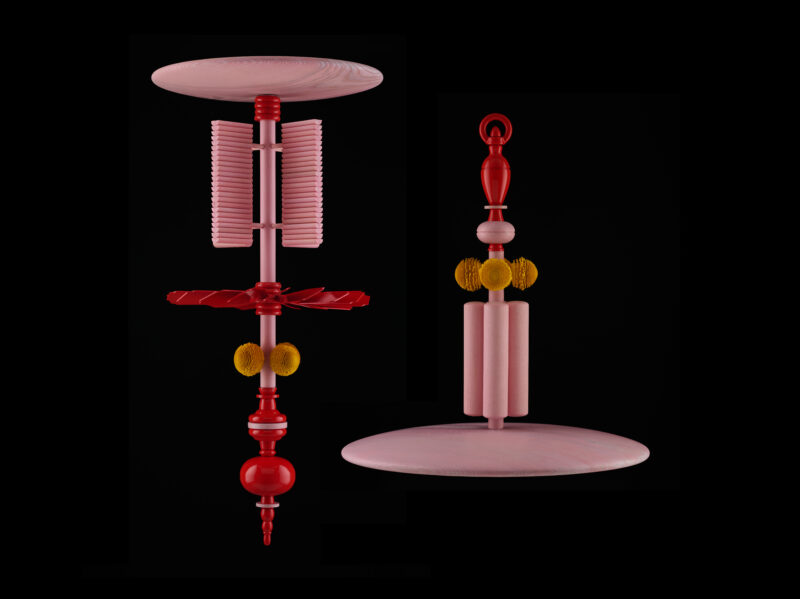

Decoding everyday life and examining the objects we live with—this is probably the best way to describe Johanna Seelemann’s practice. Her projects shed light on the manufacturing and use of prosaic everyday objects, trace supply chains and explore their visual and material language.

The story she tells conveys ideas of substitution, adaptation and resilience, offering optimistic and carefully considered insights into how we might design for changing values. Her studio work takes a multidisciplinary approach, resulting in a range of outputs that encompass product and conceptual design, as well as design strategy.

© Robert Damisch

Which place do you currently call home and where do you work on your projects?

For me, home is both Leipzig and Reykjavík. In both places I continue to develop projects, each offering its own context. Most of the year, I live and work south of Leipzig—the city where I grew up, where my family is based, and which I value for its kind rhythm. Leipzig has become my retreat: a place where I can work in my design studio with focus, surrounded by quiet, greenery and few distractions. Yet I also spend a significant part of the year in Reykjavík, teaching and surrounded by friends who have made the city a second home to me, since ten years. I appreciate the stark contrast between the two settings—in landscape, in culture, in infrastructure, in ways of being. Moving between the two creates a friction and appreciation that sustains me.

Where is your studio located & how does it look?

My studio is set in a coach house—the smaller building at the back of a property where carriages were once kept, which has since been converted into a living space. It’s located near a park and a short bike ride from the lakes on the southern outskirts of Leipzig, just ten minutes by train from the city center. Spread over two floors, the space is kept fairly office-like, yet it’s full of plants, objects and material samples from a wide range of projects. A collection of design-related books and sits nearby, supporting daily work. From the windows, I mostly see trees, keeping the view purely green through most of the year. During the summer months, I’m fortunate to be able to move my work to the terrace, where I can enjoy the open air and sunlight.

© Robert Damisch

Are there any projects that are personally important to you—whether recently completed or currently in progress?

My practice often has a theoretical and an applied dimension. On one hand, I currently do work that aims to de-center the human from design efforts, opening it to more-than-human perspectives, for example exploring how the built environment can nurture biodiversity in cities and support all of its inhabitants rather than harming and excluding them—a focus that is very important to me. On the other hand, I am fascinated by materials—their origins, their makers, rare techniques, and the aesthetic languages they carry—and by the tension between an object’s visual language, expectations, and purpose. One project that is particularly dear to me, and which I’ve been working on for a while now, is based in the Erzgebirge region, approximately 120 km south of Leipzig, and engages with rare, unique woodcraft techniques that are now under threat. The aim is to free these techniques from their traditional object typologies and place them in new contexts—for example, moving beyond seasonal Christmas market products toward furniture or other non-seasonal designs. The project is about finding new interpretations and applications for these crafts, helping them evolve while remaining true to their roots.

© Nicola Colella, Park Associati

© Robert Damisch

© Robert Damisch

Do you have a favorite place in your area where you like to relax and linger?

I love spending time at Markkleeberger See, a large lake with boats, protected areas, and beaches. It’s wonderful for cycling around, running, jumping into the water in the evening after work, or collecting sea buckthorn. There’s always a quiet spot by the reeds to be found. For longer tours, there’s a whole seascape of neighboring lakes to explore—including Störmthaler See and Cospudener See—each with its own distinctive character. Another absolute favourite is kayaking through the Auwald, a humid, species-rich floodplain forest that feels almost like a jungle along the rivers—and you can paddle all the way to the lakes or to the city. Seen from the water perspective, the old industrial areas in western Leipzig, like Schleußig and Plagwitz, are striking, with their restored red brick buildings and bridges. Then, Leipzig’s classical music scene is almost impossible not to linger in. From the world-class Gewandhausorchester to summer open-air concerts in Rosenthal, from opera and ballet to musicals, and of course Bach’s legacy at the Thomanerkirche—the quality of live music here is outstanding and a real treat. When leaving the city, Bad Dürrenberg is just a short trip from Leipzig. One of my favorite spots there is the historic Kurpark, home to Germany’s longest connected salt evaporation tower, called Gradierwerk, stretching over 636 meters. This impressive structure, dating back to the 18th century, was originally built for salt production and now offers a unique microclimate beneficial for respiratory health.

© Ansgar Koreng / CC BY-SA 4.0, Zöbigker Hafen, Cospudener See, Markkleeberg, 1709102012, ako, adjusted colours, CC BY-SA 4.0

Are there any urgent political issues or problems in your region?

Like in any place, in Leipzig and the surrounding region, a variety of issues are present, though not always immediately visible. The trade city has long been known for its openness and cosmopolitan spirit, shaped by history, including the peaceful revolution and a strong sense of community. Yet, particularly towards the outskirts, there is growing support for the far-right among all ages, including young people. Part of this is linked to the region’s history: Leipzig was part of the former GDR, East Germany, which was under Soviet influence until reunification in 1990. The decades under a communist political and economic system, followed by reintegration into capitalist Germany, created social and economic inequalities and left a sense of dislocation for many. Far-right politicians have tapped into these sentiments, skillfully using social media to present themselves as a serious alternative and connect with people’s concerns. At the same time, social issues such as gentrification, a tightening housing market in the fast-grwoing city, social inequality and over bureaucratization quietly affect daily life. Still, Leipzig’s history of solidarity, civic engagement, and creative energy, and often grand ambitions, offers a foundation for constructive approaches and positive change.

In your opinion, what has developed well in the last 5 years—and what has not?

In the past five years, Leipzig has continued to grow in vibrancy and creativity. The transformation of former industrial areas and mining pits into parks and a seascape of 30 lakes has reached a point where recultivated nature appears natural, self-sustaining, and healthy. Along with the rise of research hubs, startups, and cultural institutions, this has made the city feel curious and welcoming to newcomers. Cafés, shops, and galleries are thriving, giving neighborhoods a lively atmosphere. At the same time, rising rents and the replacement of independent shops with mainstream stores have put pressure on the city’s character. Infrastructure and public services are increasingly strained, and citizen participation in planning doesn’t always lead to tangible results. One of my favourite places, the Auwald, Leipzig’s vast floodplain forest, is facing severe drought stress and widespread tree mortality. Altered water flows and pest outbreaks are further weakening the forest’s resilience.

Do you know a hidden gem when it comes to local manufacturers—whether it’s arts and crafts, sustainable products or food?

The Leipziger Baumwollspinnerei, once Europe’s largest cotton mill in the early 1900s, has transformed into one of the city’s most exciting art areas. It’s absolutely worth a visit, with art galleries, ateliers and creative spaces. My personal highlights include Intershop Galerie, Galerie eigen+art, and the porcelain studio of Claudia Biehne. In the heart of the city, inside the beautiful Mädlerpassage, you’ll find the Sieben Sinn Store—a shop dedicated to regional craft and design. Also worth discovering is Atelier Anne Kaden, where jewelry and utensils are turned into highly distinctive, organic pieces.

Is there anything particularly innovative in your region? Also in comparison to other places you have already visited?

Since reunification in 1990, Leipzig has reinvented itself from a city of decaying façades and industrial scars into one of striking architecture, cultural energy, and new landscapes. Former mining pits have become popular lakes, research institutions and startups are thriving, and the city’s openness continues to attract young people. Even the zoo has become a model of innovation, with projects like Gondwanaland and Pongoland leading the way in conservation and research.

© Dguendel, Bad Dürrenberg, Kurpark, das Gradierwerk, Bild 2, adjusted colours and perspective, CC BY 4.0

© Krzysztof Golik, Predigerhaus in Leipzig (1), CC BY-SA 4.0

Do you have a secret restaurant tip that you would like to share with us?

It would be a pity to single out just one, so here are a few tips from different parts of Leipzig: In the west is Maza Pita, a beloved restaurant in the Schleußig district, offering Syrian and Levantine cuisine, with a focus on fresh, oriental dishes rooted in Mediterranean tradition. In the north, there is Mytropolis, a Greek restaurant, which has authentic flavors, generous dishes and brilliant service—all served in a Gründerzeit-era villa in the north. Shady, south of Leipzig’s center, specializes in traditional Arabic cuisine, inspired by dishes from Nazareth. Further south, there is Café Maître, a classic, an atmospheric French-style café and patisserie, in an Art Nouveau setting. Lastly, Zest is a fine vegan restaurant in Connewitz, even further south, known for its innovative international cuisine and seasonal variety, with a menu that changes deliberately and regularly according to the time of year and culinary concept.

© MAZAPITA

© MAZAPITA

Is there a local shop whose products are only available in your region?

The flea market at the Agra, held every last weekend of the month, is a local treasure. In the early mornings, over a thousand traders from across Germany come to trade among themselves; later, it opens up to everyone, including film crews hunting for props and costumes for their sets. Recognized as one of the largest antique and second-hand markets in Europe, it offers everything from vintage furniture and rare collectibles to quirky second-hand finds.

What are your 3 favourite apps that you use every day and couldn’t live without?

Apple Podcasts, Ulysses, and Instagram—the latter for work purposes only. I use Komoot every other day for outdoor activities. And I wish I were using my language apps—Babbel (for Swedish), Busuu (for Japanese), and Drops (for Icelandic)—as often as I imagine I should.

Do you have any favourite newspapers or online magazines? And how do you keep up to date with politics or social and cultural issues?

– Aeon Magazine

– The Future Observatory Journal

– Disegno Journal

– Lowtech Magazine

– Nomad Magazine

– e-Flux Journal

– Noema Magazine

– Ilmm Magazine

– Süddeutsche Zeitung

– Die Zeit

– “Alles gesagt?” & “Die sogenannte Gegenwart”, both podcasts from Die Zeit

© Ichwarsnur, Opernhaus Leipzig Langzeitbelichtung Tag, adjusted colours, CC BY-SA 4.0

Imagine you could be mayor for a year—what would you change?

I would improve bike paths, and even develop a parallel bike-street system similar to those in the Netherlands or Denmark, and make public transport free. I would introduce the Swedish “allmännsrätt”—the right to roam—and see how the city develops. It might require new guidelines balancing private property, conservation, and public access, potentially leading to more creative urban design, wildlife-friendly infrastructure, and greater citizen stewardship. I’d also open up more urban grounds and intentionally ease it for other species to co-inhabit the city. Further, I would make sure that Leipzig is better connected internationally, infrastructurally through transport, but also as a culturally relevant voice.

One last question: If you could choose another place to live—regardless of financial or time constrains—which one would you choose?

I am so deeply curious about the world and could see myself living in many places, connecting with different customs, cultures, languages, and crafts. If I had to choose a specific retreat for now, it would be the Swedish archipelago, the Skärgården, east of Stockholm, on one of the smaller islands near Möja—dotted with red houses with green doors and yellow houses with turquoise roofs, gently edged by järsgård roundpole fences, saunas, and wild fruits—a kind of immersion and resonance I aspire to.